Jordan wasn’t vocal about social justice like today’s N.B.A. stars, but his secret brand of activism is a key reason they have the spotlight now.

On the first road trip of his N.B.A. career, in the fall of 2001, Etan Thomas looked out the window of the Washington Wizards’ team bus and was stunned by the massing crowd around the hotel.

He asked Christian Laettner, the veteran forward: “Is this how the N.B.A. is?”

Laettner laughed. “No, young fella,” he said. “This isn’t for us. They’re here for M.J.”

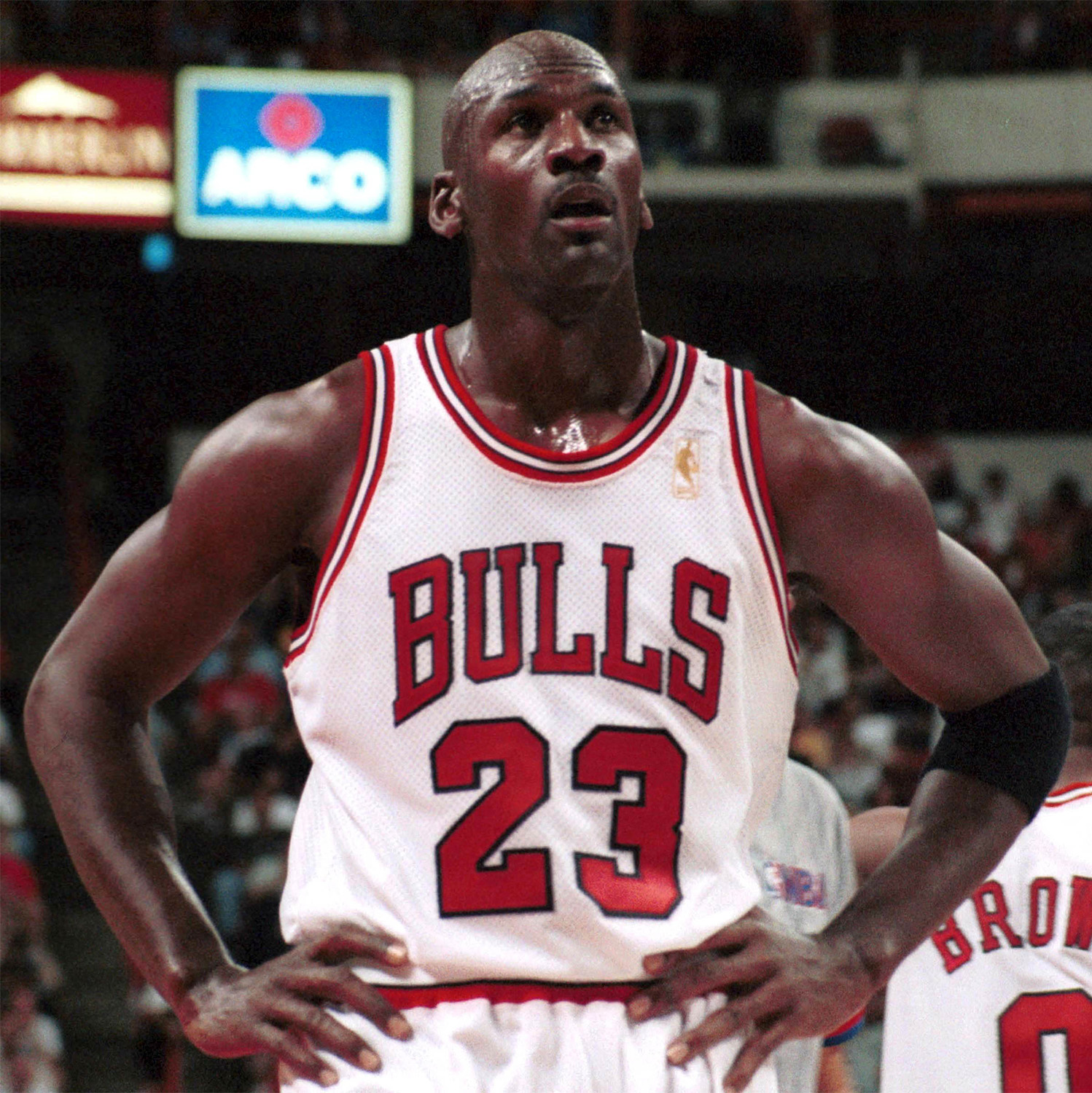

This was lesson No. 1 of Thomas’s two-year tour with Michael Jordan, who had returned to the league from a three-season absence following his last dance with the Chicago Bulls. Along with him came the deluge of lights, cameras, action.

The young, inquisitive Thomas couldn’t help but wonder: What about the activism? Why wasn’t Jordan doing more with his spotlight?

“I was thinking that Michael didn’t lend his voice to causes where he could have helped,” Thomas said in a recent interview, 20 years removed from his time with the man on whose shoulders the sport dramatically rose in popularity worldwide.

Jordan played his final N.B.A. game on April 16, 2003, scoring 15 points in a 20-point defeat in Philadelphia. That season, with him turning 40 in February and dealing with a knee that Thomas remembered could swell like a grapefruit, Jordan averaged a modest (for him) 20 points per game. He played 37 minutes a night and in all 82 games — part of a legacy that should admonish, if not embarrass, today’s load-managed N.B.A. elite.

Jordan retired as a six-time champion with many believing, and now still insisting, there was no one ever greater. Such conviction has only been heightened by the widespread appeal of “The Last Dance,” a 10-part ESPN series about Jordan’s Bulls that was broadcast in 2020, and the current feature film “Air,” starring Ben Affleck, Matt Damon and Viola Davis.

The flip side of Jordan mania was the derision directed at him for appearing not to use his enormous popularity and platform as a premier Black athlete for the benefit of social or political change. For all the interviews he did, what arguably remains the most memorable quotation attributed to him — “Republicans buy shoes, too” — ostensibly rationalized his unwillingness to endorse Harvey Gantt, an African American Democratic candidate in a 1990 North Carolina Senate race against Jesse Helms, a white conservative known for racist policies.

On a broader scale, it reflected the narrative that followed Jordan into the 21st century: that he was a hardcore capitalist without a social conscience. Sam Smith, the author in whose 1995 book the quotation originally appeared, has many times called it an offhand remark during a casual conversation — more or less a joke — and said he regretted including it. In the ESPN series, Jordan said he made the comment “in jest.”

In recent tumultuous and polarizing years, Jordan has become more public with his philanthropy and occasional calls for racial justice. And given two decades to consider the precedents he set, the boardrooms he bounded into and how he ascended from transcendent player to principal owner of the Charlotte Hornets, the context has shifted enough to ask: Did he actually blaze a different or perhaps more impactful trail to meaningful societal change?

Jordan created his own controversies, mostly related to high-stakes golf, including the case of a $57,000 debt he paid by check to a man who was later convicted of money laundering. But even his legendary casino preoccupation seems more quaint now given professional sports’ unapologetic marriage to the online gaming industry.

Jordan, at 60, deserves to be viewed through the lens of an evolved narrative, given how high he has raised the bar for athletes outside the lines, a legacy that will resonate far into the future.

Twenty years after his last professional jump shot, he is arguably still the most leveraged player in sports. If he were so inclined, he might even have the muscle, upon walking away from basketball, to make a competitive run for the seat once held by Helms. His pitch, of course, was always bipartisan.