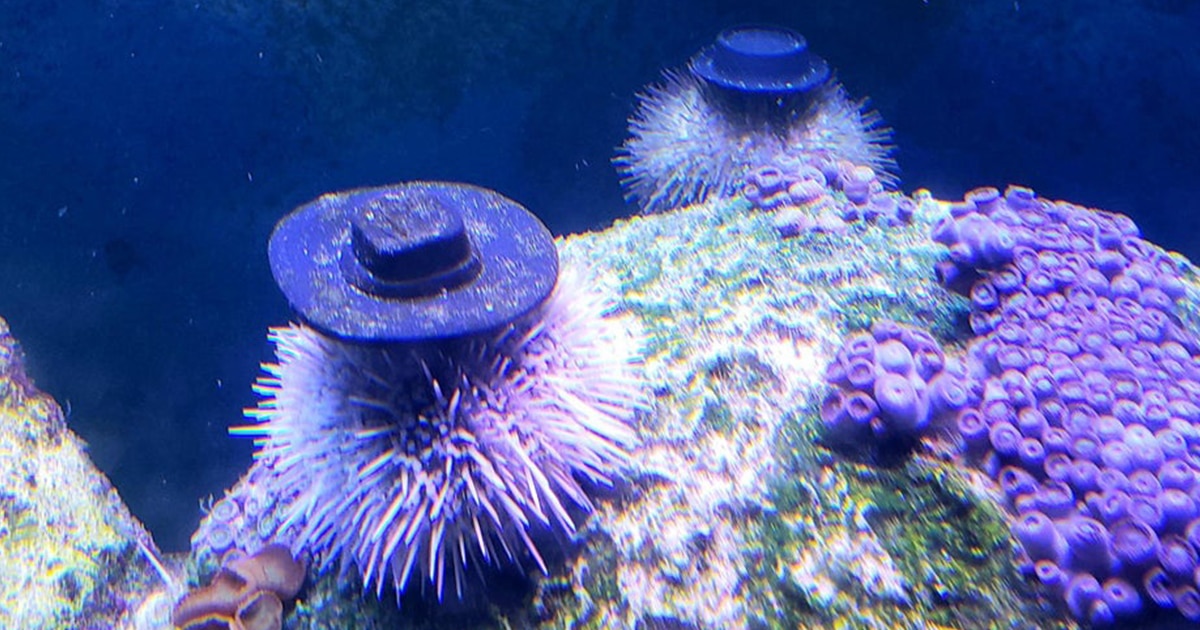

Wilson Souza’s first design was meant to be functional rather than stylish. Souza compared it to a wok cover. Since then, he’s had to become a fashion designer of sorts for the echinoderms (a phylum including sea urchins, starfish and sea cucumbers), tailoring cowboy, viking and top hats with an arched bottom to give the urchins enough purchase for their spines to hold on.

Emma Verling, who holds a doctorate in marine ecology from University College Cork, described to Newsweek how sea urchins mount hats, shells, rocks and other objects atop their spines, manipulating objects with hundreds of tube feet—flexible stalks with suction cups.

Verling described the process as “quite entertaining to watch,” as the dextrous echinoderms coordinate their appendages to lift objects onto their spines, sometimes making multiple attempts when their coverings slip off.

“I noticed at night they would let go of some of the stuff they carried during the day,” Souza told Newsweek. “I started wondering if it has anything to do with the full spectrum lights that we use for corals. I shared it with my wife Sylvia, who said, ‘Well, if they are trying to protect themselves from the UV rays, then why don’t you design and 3D print some hats for the poor little things?'”

“I remember sitting for hours with only my flask of tea for warmth and the urchins for company,” Verling recalled for Newsweek, describing the experiment she conducted at Lough Hyne Marine Nature Reserve on Ireland’s southern tip, where a saltwater lake connects to the Atlantic Ocean, creating an oxygen-rich, warm water environment for a variety of species, including the purple sea urchin observed by the area’s first marine biologist researchers in the 19th century. Urchins there preferred covering themselves with the widely available shells of saddle oysters.

“I saw them covering with all sorts of things over the years: shells, stones, bits of macroalgae, bottle tops and pieces of wood,” Verling said. “It would appear to be an energetically costly thing to do, and that’s why it’s so interesting to study it.”

Out of 20 fish, only two pajama cardinalfish survived. Souza’s tank is now populated by shrimp, hermit crabs, anemones, snails, emerald crabs and his hat enthusiast urchins, which include tuxedo urchins, a black sea urchin and a white shortspine sea urchin named “Spiky.”

While sea urchins can spend their days sporting hats in Souza’s aquarium, they fulfill less fashionable roles in their wild marine environments, grazing on seaweed (macroalgae) and opening seafloor habitats for other species (Verling describes them as the “beavers of the ocean”), balanced by keystone species like otters keeping them in check and preserving kelp forests.